In their significance, brilliance and invention, the paintings in ‘European Masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York’ are as revelatory today as ever. Drawn from one of the world’s greatest art museum collections, the 65 paintings featured are exhilarating in the scope of their claims on the knowledge, pleasure and meaning found in art. Their extraordinary reach confirms the power of art.

LIST OF WORKS: Discover all the artworks

DELVE DEEPER: More about the artists and exhibition

THE STUDIO: Artworks come to life

WATCH: The Met Curators highlight their favourite works

This story of 500 years of European painting, from the fifteenth to the twentieth century, reveals the key shifts in artistic enquiry across a formative period in Western art history. Earlier, painting was used for miniature illustration and the decoration of illuminated manuscripts, or for wall-based murals, mosaics, tapestries, stained glass or polychromed sculptures. This three-part account — Devotion and Renaissance; Absolutism and Enlightenment; and Revolution and Art for the People — shows how the paintings in this story became increasingly accessible, both materially and in their subject matter. While ‘European Masterpieces’ is largely focused on the course of that trajectory, it also reveals how meaning is made; namely, the more we know of the conditions in which these works of art were created, the more likely our stories will find company and wisdom in theirs.

Across 500 years

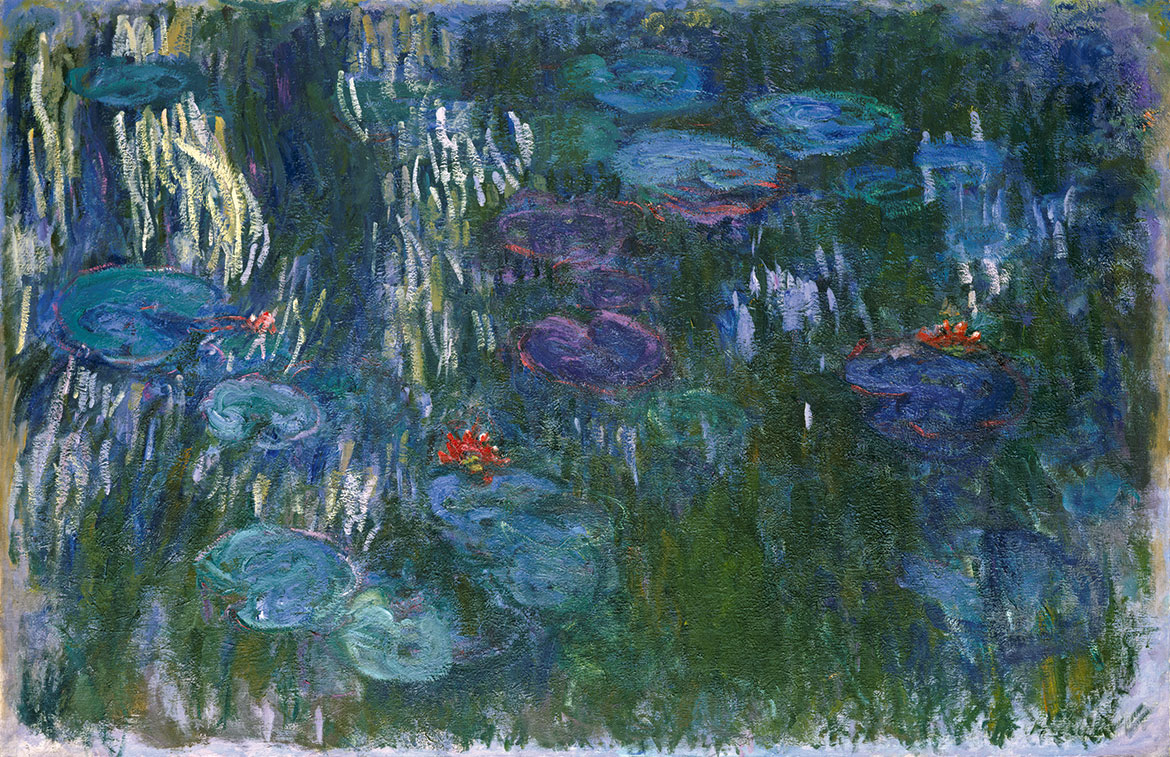

The earliest painting in this exhibition, Fra Angelico’s The Crucifixion c.1420–23 (illustrated), is in telling contrast to the latest, Claude Monet’s Water Lilies 1916–19 (illustrated). Everything that separates these two works — from their scale and subject matter to their mode of production — speaks to the evolution of Western art over five centuries. Whereas Fra Angelico entreats us to witness a transcendent event in the life of Christ, Monet invites us to experience a mere moment in the life of his much-loved garden: one is other-worldly and eternal; the other drawn from this world but entirely ephemeral.

In a departure from the segmented and hierarchical images of Christ’s Passion that preceded it during the Middle Ages, the figures gathered around the base of the cross in The Crucifixion occupy a common ground plane. While this work intends to provoke spiritual reflection just as much as its precursors did, here the composition makes the story all the more palpable. The mounted soldier in a blue tunic, to the right of the cross, acts as an interlocutor in dialogue with the viewer, drawing us into the turmoil unfolding in the moment of Christ’s death. His impassive bearing stands in violent contrast to the grief-stricken Saint John, below, whose love and empathy for the collapsed Virgin implores ours.

Fra Angelico was a friar in the Dominican Order whose workshop painted altarpieces and frescoes for churches and monasteries, and his work was reliant on charity and guided by vows of obedience, chastity and poverty. In this small, skilfully devised panel of painted and gilded wood, Fra Angelico sets the exhibition’s course, begging us not to turn away from the face of suffering. Even for a nonbeliever, an apparently immutable image can encompass manifold meanings. Beyond this appeal to devotion and moral reflection, which is at the heart of a spiritual life, Fra Angelico’s call to our common humanity carries through to the present day.

Monet’s Water Lilies, which closes the exhibition, is derived from another kind of belief system — one which values empirical evidence over divine intervention. From his studio and garden at Giverny, outside Paris, Monet sought out an instant in nature’s relentless flux, taking realism to the edge of abstraction. This profoundly modern desire for instantaneity was at the heart of the Impressionist movement, itself named pejoratively for Monet’s Impression, Sunrise 1872. Unlike the fixed and timeless suspension of Fra Angelico’s vision, Monet’s worldview is more simply possessed of a light breeze that gently disturbs the mutability of the natural world, painted en plein air, as light and wind play over the water’s surface.

Monet asks us to live fully in the moment, to see the world reflected in the smallest corner of a pond. His approach might be compared to the Western practice of mindfulness, with its roots in Eastern religious traditions. In contrast with Fra Angelico’s fast-drying and unforgiving medium of tempera, Monet’s use of oils allowed him to paint with a verve and energy much closer to the dynamic experience of modern life. In late works, such as Water Lilies, he also altered the relationship between the painted image and reality by abandoning a fixed viewpoint. Taking their cues from successive innovations and influences, including Japanese ukiyo-e prints and photography, artists such as Monet were freed from the linear perspective that had defined pictorial space since the Renaissance, and were thereby enabled to construct new ways of seeing a fast-changing world.

Where past meets present

Looking back over the course of these five centuries of European art history, it is clear artists have always turned to the past to find a way through into the future. Cézanne looked back when striving to surpass Impressionism via ‘something solid and lasting like the art of the museums’, which he found in the work of Poussin; and Poussin looked back to a formal grammar Raphael rediscovered in the distant past of the classical world. Looking forward, with the benefit of Cézanne’s groundbreaking legacy, Georges Braque would seize on Picasso’s idea of Cubism while painting the overlapping geometric volumes and rooftop planes of houses at L’Estaque in 1908, only a short distance from the village of Gardanne. At such turning points, these moments of innovation and reply, the vital correspondences between the artist, the world and the viewer, are renewed.

Art tells our stories, sacred or profane, be they drawn from the artist’s eye or mind, from literature, poetry or life. All these patterns of creative intention are present in ‘European Masterpieces’, which richly rewards the act of looking. It is through looking that artists themselves discover the alchemy that occurs across time. This act in turn can have a profound effect on how they imagine their own place within a creative continuum. ‘European Masterpieces’ includes works made in reply to a vast array of intellectual and aesthetic energies, in an arc that opens with the Early Renaissance and closes toward the final years of Impressionism. These are paintings that, in the end, forcefully remind us that all art, at one point in time, is contemporary.

Edited extract from European Masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York ‘Painting as a form of reply’ by Chris Saines CNZM, Director, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

Paul Cézanne

Nicolas Poussin

Raphael

This Australian-exclusive exhibition was at the Gallery of Modern Art from 12 June until 17 October 2021 and organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in collaboration with the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art and Art Exhibitions Australia.

Featured image detail: Nicolas Poussin Saints Peter and John Healing the Lame Man 1655

#QAGOMA #TheMetGOMA